Let the Wind Carry Me (Chiang Hsiu-Chiung & Kwan Pun-Leung, 2009)

New York City has once again been blessed with a killer film series at the Metrograph. “Daring Motion” is dedicated to the cinematographer Mark Lee Ping-bing, best known for his collaborations with Hou Hsiao-hsien, but who has also worked with Wong Kar-wai, Tran Anh Hung, Kore-eda Hirokazu, Jiang Wen, and many more luminaries of film both Asian and beyond. Accompanying the series is this 2009 documentary about Lee and his work, available to stream through Metrograph’s At Home service. Film series built around directors and actors are of course common, but ones built around below the line artists are more rare. Let the Wind Carry Me though makes a great case for Lee’s status as an auteur cinematographer, an artist whose imprint is recognizable regardless of which other people he happens to be working with.

Directors Chiang Hsu-chiung and Kwan Pun-leung are eminently qualified to explore Lee’s work. Chiang made her film debut in Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day, worked as script supervisor for Yang’s A Confucian Confusion and Yi yi, and was an assistant director on Hou’s Millennium Mambo. Kwan was one of the credited directors of photography on Wong’s 2046 and served as cinematographer on a number of Ann Hui’s 2000s films. His other film credit as a director is for Buenos Aires - Zero Degree, a film about the making of Wong’s Happy Together. While Chiang and Kwan devote ample time to Lee’s biography and his personality, the film is just as much interested in what characterizes him as an artist. He joined Taiwan’s CMPC studio as a young man and worked his way up through the camera department, challenging the organization’s staid old guard contemporaneously with the young filmmakers of the New Taiwan Cinema (Hou, Yang, etc). He won an award for his work on his second credited film as a DP, 1984’s Wang Tung wuxia film Run Away, which I haven’t seen yet but judging by the clips used in the doc looks absolutely amazing. In 1985, he began a thirty year collaboration with Hou, one of the most artistically fruitful director/cinematographer pairings in film history. At the same time, he also began working in Hong Kong, making mainstream genre films as well as art house movies. His list of credits is formidable: not only the Hou films but also ones with Ann Hui (Eighteen Springs, Summer Snow), Sylvia Chang (Tempting Heart, Princess D, Love Education), Tian Zhuangzhuang (Springtime in a Small Town), Patrick Tam (After This, Our Exile), Yuen Woo-ping (Wing Chun), Wong Kar-wai (In the Mood for Love), Corey Yuen (Fong Sai-yuk II), and many many more.

Lee as a person seems as remarkable as he is as a filmmaker. No one has a bad thing to say about him: all the interviewees are effusive in their praise. Hou in particular seems to recognize the depth of Lee’s contributions to his work. In affect, Lee is somewhat unexpected. Bearded with shaggy hair, he rumbles around in jeans and cargo shorts, looking every bit like a working man crew member rather than a highly successful and acclaimed artist. Both Sylvia Chang and Wong Kar-wai describe him as dressing “like a soldier”. He spends much of the film talking about and visiting with his mother, and late in the movie we get some brief words from his son, neither of whom he gets to see as much as he’d like. In fact, much of what Lee seems to want the movie to convey is his regret over prioritizing his work over his family, but his inability to do otherwise. He’s a man who loves what he does and simply cannot do anything else.

More interesting though are his thoughts on cinematography itself, which comes down to two basic things, the fundamental features of cinema since the very beginning: light and motion. Light Lee wants to capture as naturalistically as possible. Which does not mean, for him, the flat, bland lighting of classical “realist” film. Instead, he wants to capture natural light in all its various forms and shades, colors and shadows. Whether natural sunlight or lighting sourced in objects around the set—Lee isn’t dogmatic about realism, he’s more interested in the light for its own sake, not as part of an ideology. In Flowers of Shanghai, for example, Hou wanted to use oil lamps to light all the scenes, recreating the lighting as it would have been at the time the movie was set. Lee agreed, but knew that the actual oil lamps themselves wouldn’t recreate the image Hou had in mind correctly, so he devised an artificial system which would supplement the source lighting. The two couldn’t really come to an agreement over the final image (Hou kept making it darker in post-production) but the result is undeniably one of the most beautiful films of the past 30 years.[1]

All of Lee’s statements about light are illustrated with clips from his films, and one of the more fascinating things about them is that, because the doc was made 15 years ago, all the clips are sourced from unrestored prints. We’ve been so blessed recently to have digital restorations of so many Taiwanese classics, but actually getting to see film of them is pretty rare (maybe not in New York, but for the rest of us). So while I’m extremely familiar with, say, the digital look of the restored The Time to Live, The Time to Die, seeing the original celluloid images, with their natural fluctuations in grain and light is a revelation. On film, the light seems to move, seems alive, in a way the sterile perfection of digital can never really capture. This isn’t exactly the kind of motion Lee talks about in the documentary, but it is striking nonetheless.

What Lee has in mind is more the old DW Griffith idea of cinema capturing the wind in the trees. We even get several shots of exactly that, along with the movements of shadows (the clouds blowing by as seen on the green earth in Dust in the Wind), and actors. Shu Qi talks about how he doesn’t demand a certain blocking from his actors, rather he moves his camera around their own movements, creating a sense of openness and collaboration between the two (though he does politely admonish her for eating the popcorn on a set that he was using as part of a lighting scheme). When, after a decade of having almost no camera movement in his films, Hou suddenly set his frames adrift in the mid-90s, bobbing around up/down, left/right, or diagonally, usually at a fixed distance from the actors in the frame, that appears to have been a Lee innovation (we see a French assistant relate how he was baffled that Lee wanted to simply be pushed around randomly with the camera in tow while he filmed the actors). It’s this openness that may be Lee’s greatest strength as an artist, and informs ever aspect of his work and his relationships with his fellow crew members. It’s an openness to light, to performance, to his directors’ minds, to the experience of making a movie.

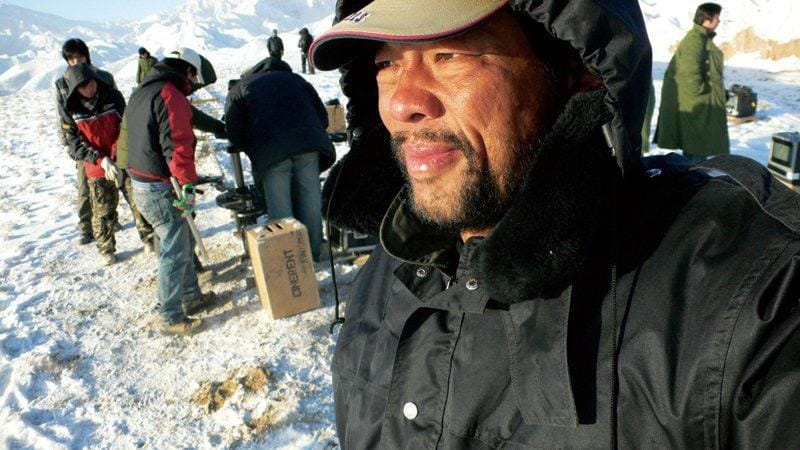

Jiang Wen touchingly connects the two. During the making of The Sun Also Rises, they were meant to be filming in the desert when a sudden and freakish snowstorm blew through their location. To Jiang, this was a disaster—days of delays costing tons of money. But Lee saw it as an opportunity, a chance to capture on film a wildly improbable natural event and thus, paradoxically, make the film feel more like real life. They shot in the snowy desert, and it looks gorgeous (it’s Jiang’s most beautiful film by far). More touchingly though, Jiang talks about how much he admires Lee as a person, his ability to treat everyone with the utmost respect and humanity, something he finds lacking in himself. It may not be a sentiment Lee’s own son shares, missing his father most of his life while growing up with his mom in Los Angeles. But that contradiction too is also like life.

Hou is the most fascinating interviewee in the film, which is fitting given his long association with Lee. His discussions are even more poignant now, in the wake of the revelations that he has had to retire from filmmaking due to worsening dementia symptoms.

The most intriguing of Hou’s comments is only tangentially related to Lee, but has profound implications for how we might think about Hou’s work. Near the end of the movie, he explains that for him, the film image is just as “real” as reality itself. The act of making a film is therefore a godlike act of creating an entire world, bound only by the limitations of celluloid, montage, and running time. This is an idea I don't think I've heard or read Hou express before, and the way this potentially intersects with his work's explorations of history and memory, both of Hou’s own life, that of his colleagues and friends, and of Taiwan as a whole, is something to be explored some other time. ↩︎