Japan Cuts 2024 - Part 3

It’s taken me a bit longer than I’d hoped to roll out this third and final installment of my Japan Cuts coverage. Mostly because I was enjoying watching the Olympics so much this past weekend. But in a wild coincidence, both of the movies I’m reviewing here are about Olympic sports.

Moving (Somai Shinji, 1993)

OK so not really, but there is a whole lot of running in Somai’s Moving, the latest of the director’s films to be restored and get a festival release. We all owe a debt of thanks to Cinema Guild here in the US and Third Window in the UK for making Somai’s films widely available for the first time. The Japanese cinema of the 80s and 90s seems a ripe area for discovery for the West, where for so long our histories ran from Ozu to Oshima, then just skipped ahead to the horror films of the late 90s, with the odd nod to Kitano Takeshi, Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Studio Ghibli, or the now-disgraced Sono Sion. This year’s Japan Cuts archival program highlights three films from the 85-95 period that should certainly have a higher profile (I wrote about Mermaid Legend last week), and Moving is the best of them.

While the other two Somai films I have seen, 1981’s Sailor Suit and Machine Gun and 1985’s Typhoon Club, are indebted to the exploitation film traditions of the 1970s, the former playing with yakuza film tropes and the latter teasing pink film thrills before veering into something much weirder and more profound, Moving is firmly in the art house traditions of the early 90s. It played at Cannes in 1993 (in Un certain regard) and tells the more or less realistic story of a couple’s breakup through the eyes of their 12 year old daughter using long takes to help build authenticity in setting and performance. Somai’s takes aren’t as austere as his peers in the Taiwanese New Cinema, his camera is much more flowing and his editing more classical than Edward Yang or Hou Hsiao-hsien, but the film does, I think, share something of the same DNA as their more child-centric movies (A Summer at Grandpa’s, Yi yi, Growing Up).

But Somai’s film is much more character-focused than Yang or Hou ever really were, fully committing to the perspective of Renko, his precocious young protagonist. She’s played by Tabata Tomoko in an exceptionally energetic and forceful performance. As the film begins, her father is moving out of the family house. They all have a last meal together, one which Renko plays more of a parental role than either her mom or dad. The next day, she skips out of school to join her dad’s moving truck, which she chases after, in the first instances of Renko running, which Somai films in long takes demonstrating Tabata’s impressive endurance (the word is that cardio capability was a key part of Somai’s audition process for the film). Renko runs everywhere. She runs when she’s happy, she runs when she’s sad. She runs away from home and from school and from one parent to another and back again. She’s always, ahem, moving.

Her parents try to keep up with her, but they can’t, and her mother especially, who has primary custody of the girl, has trouble relating to her and creating a viable structure for their new, dad-less life. Renko acts out in the usual ways, and it all comes to a head when mother and daughter go on vacation to Lake Biwa, which is having its annual fire festival. The dad, it seems, is there too, and Renko runs away from them both. She sets off on a long journey through the night, first being helped by an elderly couple, then watching some fireworks. There her mother spies her across the crowd and Renko promises to grow up as fast as she can before running off again, this time on a lone trek through the woods and to the lakeshore. This long sequence is where Somai departs from his realist contemporaries for something more impressionistic, more beholden to the protagonist’s imagination. The only thing really like it in Yang or Hou’s work is the brief dream sequence in Dust in the Wind.

But it’s very much in the same vibe as Typhoon Club, almost all of which has the same kind of heightened, uneasy reality as Renko’s journey. It makes absolute emotional sense, and the fact that it’s almost completely dialogue-less is a testament to Tabata’s skill: not only is she clever and charismatic in the first half of the film’s dialogue scenes, she also commands the movie’s weirdest, non-verbal scenes. Following Japan Cuts, Moving is going to make the art house rounds, beginning with a mini-Somai series at the Metrograph in New York (where it will be joined by Typhoon Club and PP Rider). Run, don’t walk, to see it.

August in the Water (Ishii Gakuryū, 1995)

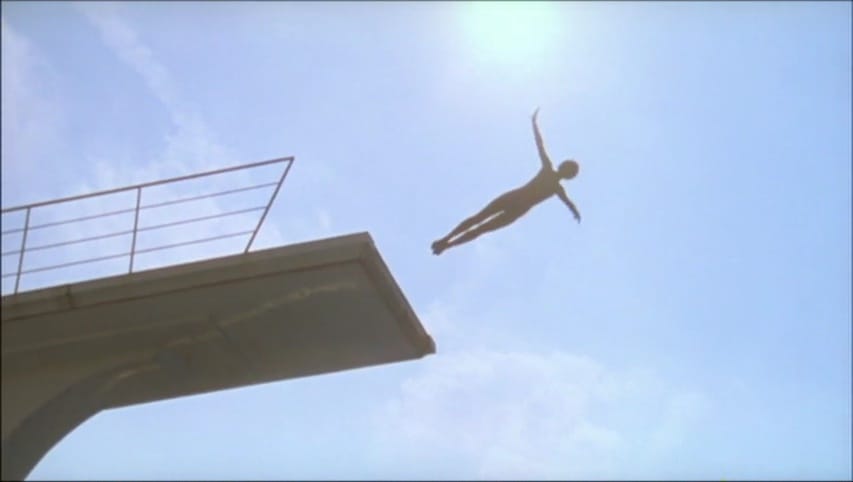

While Moving takes place mostly on land, venturing into the water only at its dramatic and emotional climax, where the lake proves to be a source of resolution and renewal, August in the Water concerns itself eventually with the conflict between land and water, literally or metaphorically, depending on how much of its second half’s proposed lore you want to believe. But it starts as a slice-of-life sports drama, centered on a young diver named Izumi (a newspaper headline about her says “August in the Water”, which may be a reference to the upcoming month’s water sports event, or may be a description of Izumi herself, a nickname sourced in her imperial dominance in the pool) who moves to a new school and befriends the two boys who are enchanted with her. One, the quieter of the boys, becomes her boyfriend, while the other, thanks to another friend who is into astrology, predicts impending doom for Izumi. There’s a diving accident (on her way down, we see a flash where the pool has turned to stone, which may be her imagination and may not), and when she recovers, Izumi is eerily changed.

At the same time, the city is best with drought and people are dropping left and right of something they’re calling “stone sickness”, where it seems their internal organs are turning into rocks thanks to dehydration or something like that. From its realist beginnings, the movie becomes increasingly abstract, an ecological parable involving ancient traditions (there’s a festival here as in Moving, but rather than fire, it involves water), aliens, meteorites, a murder or two, and some kind of virgin sacrifice. We never really know what is happening with Izumi, and despite all the weirdness and the hallucinatory vibe Ishii brings to the film, the very real possibility remains that she is simply suffering from the effects of her diving accident.

If Moving recalls the New Taiwanese Cinema, August in the Water reminded me most of Obayashi Nobuhiko’s early 80s films School in the Crosshairs and The Girl Who Leapt through Time, both of which freely mixed bizarre sci-fi storytelling (though Ishii eschews Obayashi’s idiosyncratic use of special effects in favor of a more naturalistic setting) with the traditional high school romance genre. But as always with Obayashi, his films teem with hope and possibility, for his characters, for humanity, and for the future. Ishii’s story is far more pessimistic, his world on the edge of climactic disaster with only death as our salvation.