Glory to the Fat Dragon!

Since today is Sammo Hung's birthday, I figure it's a good time to repost this look at his career, originally posted on the now-defunct website Frame.land back in the summer of 2017. There were originally several video clips interspersed throughout the essay, but they seem to have been lost to time and the vicissitudes of the internet.

A man with a physique of stacked circles sculpted out of melted butter may be the most important figure in the history of action cinema. Bruce Lee is the cinema’s great symbol of virile masculinity, his musculature matched in intensity only by the power of his punches and overdubbed screams. He’s the Dragon. Sammo Hung, it naturally follows, is the Fat Dragon. Preternaturally acrobatic in defiance of all known laws of biomechanics, Sammo’s speed and agility is as much a mystery as the flight of a bumblebee, the incongruity of his everyman form and superhuman abilities innately entertaining. We look at Bruce Lee with awe, we see ourselves in Sammo. His characters are crude, lazy, dumb, alternately cruelly self-centered or pathetically self-pitying. His laughs are often of the very lowest variety: from banana peels and fart jokes to casual misogyny, gay panic, even one particularly inexplicable episode of blackface. But they can be as well as sublime as the best work of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin.

A naturally populist filmmaker, with a great empathy for the improvised communities of the poor and itinerant that made up the Hong Kong of his youth in the post-war era, his films nonetheless abound with grotesques: false noses and outrageous teeth, slurping lips and hideous moles, everyone on the take, every transaction a scam. Alone among his action star peers Sammo recedes into the ensemble in his own pictures.

Where on-screen Lee rarely faced an equal, or where Gordon Liu, Jet Li, and Jackie Chan dominate both the plots and the action of their films, Sammo is always balanced with an equal fighter, a teacher figure when he’s the star, or, more often, playing a supporting role in a larger ensemble or as the mentor to his film’s true hero. His generosity as a choreographer, director and producer gave many future stars their first major platforms: Yuen Biao, Lam Ching-ying, Leung Kar-yan (aka “Beardy”), Eric Tsang, Michelle Yeoh, and Cynthia Rothrock, as well as the last great roles for legendary star Kwan Tak-hing, while his short-lived production company with Lau Kar-wing (himself an important choreographer who did his best work on-screen with Sammo) laid the foundations for the Cinema City studio which would dominate and radically transform Hong Kong cinema in the 1980s.

He has played an integral role in Hong Kong masterpieces from at least five decades. He brought serious acrobatics to the kung fu film, helped invent both the girls with guns and hopping vampire subgenres, was instrumental in the revival of Cantonese language cinema at Golden Harvest in the mid-70s, and worked with everyone from King Hu to Wong Kar-wai in a career now almost 60 years long and still going strong.

Hung Kam-bo was born in Hong Kong in 1952, the grandson of Chin Tsi-ang, one of the first great female action stars of Chinese cinema, and Hung Chung-ho, a film director and producer in Shanghai and later in Hong Kong. Sammo’s parents also worked in the film business, in wardrobe, and at the age of nine he was sent to the China Drama Academy, a Peking Opera School run by Yu Jim-yuen. There Sammo learned kung fu as well as singing, dancing and acrobatics under Yu’s infamously stern instruction. He was a member of the school’s highly-regarded performing troupe, the Seven Little Fortunes, and as one of the older kids in the school he played a big brotherly role, both helping out the younger kids and bullying them. With the decline of Peking Opera as a popular art form, many of its practitioners found jobs in the local film industry, where their athletic and martial skills made them ideally suited for stunt work.

Sammo had done some acting as a child, appearing on-screen as early as 1961, but in 1966, at the age of 14, he worked as a stunt performer in King Hu’s seminal wuxia Come Drink with Me (which also featured a very young Ching Siu-tung, who would himself grow up to become a major choreographer/director), the success of which convinced the Shaw Brothers to abandon the lavish musicals they had been specializing in and dive headlong into the martial arts genre.

After several more years of stunt work and apprenticeships in action direction, Sammo signed with the rival Golden Harvest studio, choreographing its first film, The Angry River, under the direction of Huang Feng. Working several more times with Huang through the early 70s, usually in support of star Angela Mao while also directing the action (the best of them is 1972’s Hapkido), Sammo also continued his partnership with King Hu, who had left Shaw Brothers for Taiwan. He appears near the end of A Touch of Zen, choreographed The Fate of Lee Khan and choreographed and played the primary villain in The Valiant Ones. In 1973, he fought Bruce Lee in the opening moments of Enter the Dragon; he would later be called on to coordinate the action in the remains of Game of Death, the film Lee had left unfinished at his death.

In the 70s, Sammo Hung was one of three choreographers revolutionizing action cinema. Lau Kar-leung, working at Shaw Brothers, primarily with director Chang Cheh, brought a classical elegance to Shaws’ martial arts, based in traditional Southern kung fu forms. Lau was a practitioner of the Hung Gar style, which he learned from his father who in turn learned from Lam Sai-wing, himself a student of oft-filmed folk hero Wong Fei-hung. Lau designed elaborate routines for Shaw stars like Ti Lung, David Chiang, Jimmy Wang Yu and Alexander Fu Sheng, all of whom were primarily trained as actors, not fighters.

When Lau became a director in his own right in the mid-70s, he made a star of his god-brother Gordon Liu with a series of films exploring both the form and ideology of Chinese martial arts, dominated by long, intricately-designed performances of traditional styles (The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, Executioners from Shaolin, Dirty Ho, etc). Lau’s partner in choreographing Chang Cheh’s films was Tong Gaai (a partner was likely necessary due to the insane pace at which Chang and Shaws were churning out pictures: between 1967 and 1975, Chang directed an inhuman 47 feature films). Tong was a student of Yuen Siu-tien, a Peking Opera performer who worked, along with his many sons, on the series of Wong Fei-hung movies made by Kwan Tak-hing throughout the 1950s (Lau Kar-leung along with his father and brother Lau Kar-wing worked on the series as well). Five of Yuen’s sons built careers in the film industry, the most prominent being Yuen Woo-ping, who made his directorial debut in 1978 with a pair of films starring his father and Jackie Chan, the most famous graduate of the Seven Little Fortunes troupe.

As both choreographer and director, Yuen used much the same approach as Sammo Hung, in keeping with their similar training backgrounds. In contrast to the stately style of Shaw Brothers, with elaborate sets and costumes, matched by Lau Kar-leung’s precise movements, Yuen and Hung developed a more free-wheeling aesthetic, building off the eclectic street-fighting style Bruce Lee used in his films. To this catholic mixing of Southern and Northern styles, boxing punches and Korean high kicks, they added Peking Opera acrobatics and a healthy dose of broad slapstick comedy.

Now stuntmen didn’t just collapse when they got hit, or even simply fly through the air: they somersaulted backwards corkscrewing like a pinwheel at the power of the star’s blow. A hero didn’t merely avoid a fist and reset for a counter-punch by backing away, they did a triple backflip, only to land on an improbable cactus. The camerawork is similarly looser, shooting on location, cutting more freely both to highlight the beauty of certain movements and the impacts of various blows, but also with sophistication, match-cutting between separate duels during an ensemble fight (in The Iron-Fisted Monk among others), or creating visual gags that would be at home in a Buster Keaton film (as in the opening moments of Wheels on Meals).

Yuen was based at Seasonal Pictures, a minor studio compared to the Shaw and Golden Harvest powerhouses, and when Jackie Chan, suddenly a superstar after years of false starts and work in Sammo’s stunt crew, immediately began directing his own films, Yuen made a series of low-budget features starring his brothers, collectively dubbed “The Yuen Clan”, which feature some of the best fighting (Legend of a Fighter) and craziest effects (The Miracle Fighters) in the genre’s history. Yuen also directed a pair of films with Kwan Tak-hing, reviving his Wong Fei-hung character (the mythos of which Yuen and Chan had thoroughly parodied in Drunken Master).

1979’s Magnificent Butcher stars Sammo Hung as Lam Sai-wing (Lau Kar-leung’s father’s teacher) and 1981’s Dreadnaught stars Yuen Biao and Beardy. But Yuen never really recaptured the success of his Chan collaborations, (failing for years to make a star out of Donnie Yen) and ultimately became better known as a choreographer (The Matrix, Kill Bill, Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon) than a director, though films like Iron Monkey, Wing Chun and The Tai Chi Master are among the best martial arts films of the 1990s.

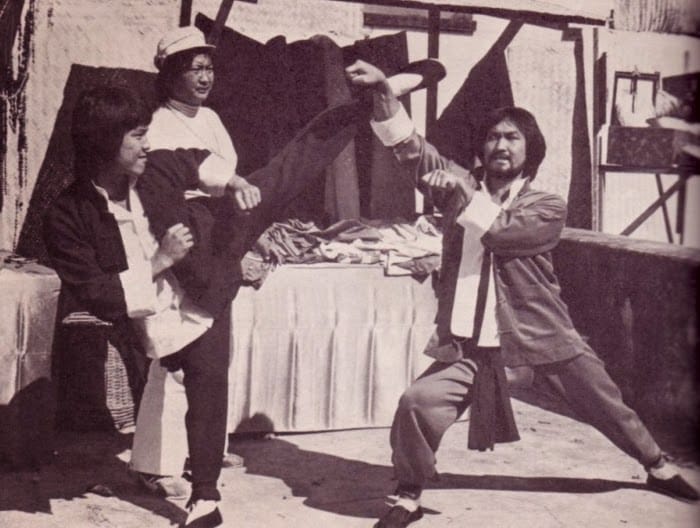

Sammo Hung was more successful as a director, making his debut in 1977 with The Iron-Fisted Monk. His early films are period kung fu movies, building off the more comic tone in Lau Kar-leung’s work (as opposed to the deadly seriousness of Chang Cheh’s films). From the beginning, Hung pairs himself with another star, Chen Sing as the eponymous Iron-Fisted Monk, or Casanova Wong and Beardy in Warriors Two.

In 1979 he directed Knockabout, a showcase for one of his Seven Little Fortunes brothers, Yuen Biao, who had spent most of the 70s working as a stuntman (he’s one of the primary Bruce Lee replacements in Game of Death). Hung also formed a short-lived production company with Lau Kar-wing (Gar Bo Films), which produced only two features (the forgettable Dirty Tiger, Crazy Frog and the masterpiece The Odd Couple) before three key collaborators (Karl Maka, Dean Shek, and Raymond Wong Pak-ming) left to form Cinema City.

The Odd Couple, in which Lau and Hung both play dual master and student roles, doomed by the inane ideology of revenge to duel forever in endless draws, exemplifies an anarchic strain in Sammo’s work that makes him spiritually akin to his contemporaries in the Hong Kong New Wave, a group of young directors (Tsui Hark, Ann Hui, Patrick Tam, etc) trained in television and the West who also burst onto the scene in the late 1970s. All New Waves tend to make their name by subverting the ideologies of their predecessors, for Sammo (and Yuen Woo-ping) this means undermining the mythos of the master-student relationship, the Confucian patrician ethos of the Wong Fei-hung ideal. For Chang Cheh, the martial codes of respect and duty lead inevitably, but honorably to violence and death. For Lau Kar-leung, those same codes contain essential spiritual truths, the key to balancing the demands of the soul and the imperatives to better the world around you. But with Sammo, the filial piety demands of master-student relationships are farcical at best (as in Knockabout, where Yuen Biao’s master (Lau Kar-wing) turns out to be a supervillain) and at their worst, as in 1980’s Beardy showcase The Victim, suicidally stupid in their abandonment of both common sense and basic human decency.

Sammo instead advocates a more pragmatic approach, his heroes must constantly improvise rather than be beholden to an abstract code of morality or right action. This often leads him to sublimate his character into an ensemble, usually literally but more abstractly in 1978’s Enter the Fat Dragon. The film is built to show off his uncannily accurate Bruce Lee impression, but rather than a self-abasing devotion to a master (in this case the absent Lee), Sammo’s impression is a synthesis of both performers’ most distinctive traits.

In 1980’s Encounters of the Spooky Kind, Sammo’s lead character, “The Boldest Man in Town” is more effectively diminished, only able to defeat the villain when he becomes an automaton, allowing himself to be possessed and used by a powerful Taoist priest. That film (building off a pair of earlier Lau Kar-leung “spiritual boxing” movies) popularized the kung fu horror film, specifically its “hopping vampire” subgenre, eventually leading to the massively successful Mr. Vampire series, produced by Sammo and starring Lam Ching-ying.

Lam was also trained in Peking Opera (tall and thin, he specialized in women’s roles) and worked for years as a stuntman (he was one of Bruce Lee’s inner circle) before finally getting a chance to show his abilities in Hung’s The Prodigal Son, in 1981, in which he performs what is generally considered among the best Wing Chun ever seen on film. The need to minimize his own prominence dovetails nicely with his desire to allow his friends to make their star turns. The Prodigal Son too can be seen as a direct response to Lau Kar-leung, where Lam's Wing Chun form is pure but incomplete. Playing Lam’s frenemy and rival master, Sammo teaches student Yuen Biao that only through improvisation can he fulfill the art’s true purpose, which is explicitly and unabashedly deadly violence. No spiritual mumbo jumbo for Sammo the materialist: kung fu is not an art, it's about poking the other guy in the eye then kicking him in the balls. But with style.

In 1982, Sammo made Carry On, Pickpocket, melding his acrobatic kung fu (paired with the lithe Frankie Chan) with a contemporary crime story and a haphazard but at times lovely romance (with Deanie Ip). The film’s best moments come in a long sequence in a disco, where Sammo first charms Ip by performing Charlie Chaplin’s Roll Dance from The Gold Rush, then by proving to be a very smooth dancer, followed naturally by a gang fight in which he quickly pummels the opposition. The film earned Hung his first Best Actor Hong Kong Film Award (the second would be for Painted Faces in 1988) and, along with the success of Cinema City’s Aces Go Places series, marked the temporary demise of the period martial arts movie in favor of a cycle of cop/Triad movies (Jackie Chan’s Police Story, John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow, Ringo Lam’s City on Fire, etc).

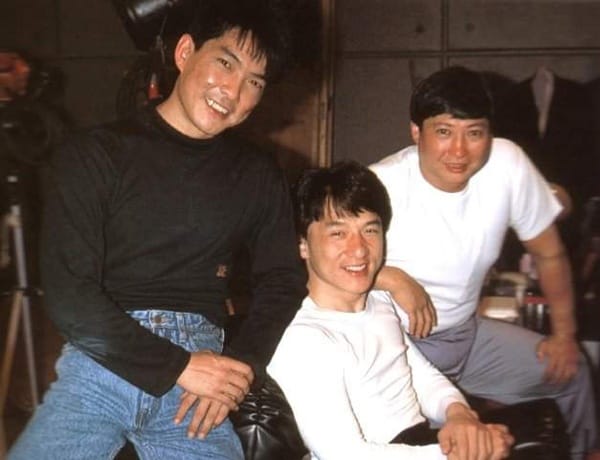

In 1983, he kicked off a series of ensemble comedies known as the Lucky Stars films in which he cavorts with a gang of cutups (Richard Ng, Eric Tsang, John Sham, Charlie Chin, etc) while Jackie Chan and Yuen Biao perform seriously dangerous stunts in the background. That same year he and Yuen also appeared in Chan’s Project A, the first of several films to unite the three biggest Little Fortunes on screen.

The best of them, and probably the best film Sammo ever directed, is Wheels on Meals, from 1984, in which the three join forces to rescue a woman from an evil rich guy in Barcelona. Chan and Yuen play the leads, with Sammo in a supporting role, though each star is given their own spectacular set piece in the finale, tailored to their strengths as a performer: Sammo a comic duel, Yuen a showcase for his elegant kicks and leaps, Chan a legendarily brutal brawl with Benny Urquidez (contrast with Project A, which Chan dominates while Yuen and Sammo disappear for long stretches and don’t figure at all in the sequel).

In 1984, Hung launched, in collaboration with improbably-named magnate Dickson Poon, D&B Films, which would produce fifty films over the next eight years, some of the most successful of which were the key films in the “girls with guns” subgenre. The first film in the In the Line of Duty series, Yes, Madam, was released in 1985 and was directed by another Little Fortune, Corey Yuen. The idea (simple enough really: “what if awesome action, but with women?”) apparently began with Sammo, who wanted to create a showcase for Michelle Yeoh (then billed as “Michelle Khan”), who had appeared in a small but memorable role in the third Lucky Stars film and was working intensely to evolve from beauty pageant winner to action star.

She was paired with American martial arts champion Cynthia Rothrock, who subsequently became one of the rare white actors to become a significant star in Hong Kong. The series eventually included the Yeoh vehicles Royal Warriors and Magnificent Warriors (sort of, it’s complicated), eventually with Cynthia Khan (her name a synthetic combination of the first film’s stars) taking over the lead for In the Line of Duty III-V, where she was paired in the fourth film with Donnie Yen, under the direction of Yuen Woo-ping.

In 1986, Hung directed Shanghai Express, an action comedy featuring just about every character actor and stunt performer of any significance in 1980s Hong Kong (including yet another Little Fortune, Yuen Bun, who would become Johnnie To’s primary action director at his Milkyway Image studio), alongside Sammo and Yuen Biao. Its plot barely makes sense and takes place in no recognizable time period (Late 19th Century American cavalry uniforms mix freely with 1930s era motorcycles), but it features the most amazing collection of stuntmen falling from great heights ever made.

The next year saw Hung’s greatest ensemble action film, the Dirty Dozen-esque Vietnam film Eastern Condors, in which he leads a ragtag team of prisoners-turned-commandos behind enemy lines. Also starring is Yuen Biao, alongside Corey Yuen, Yuen Woo-ping and, of all people, Academy Award-winning survivor of the Killing Fields, Dr. Haing S. Ngor. Yet another Little Fortune, Yuen Wah, is given a prime showcase as the film’s major villain, a giggling Vietnamese general whose long, skinny body belies immense power and lightning quick speed in an astounding showdown with Sammo.

In 1988, Hung began a productive partnership with the writing/directing/producing team of Mabel Cheung and Alex Law. In Painted Faces and Eight Taels of Gold he gives his finest dramatic performances, the latter in a kind of romance with Sylvia Chang, the former in a film based on his own time at the China Drama Academy, where he plays his master, Yu Jim-yuen and carries on a tentative romance with Cheng Pei-pei, the teacher at a rival school and the star of Come Drink with Me.

In 1992’s Moon Warriors, Hung directed from Law’s script, with Cheung producing, his most pictorially-gorgeous period film, a romantic wuxia with Andy Lau, Anita Mui and Maggie Cheung. In-between these films he made one of his best movies, 1989’s Pedicab Driver, about workers in Macao, their improvised communities and the rejection of patriarchal moral codes that are irrelevant in the face of lived experience. It’s one of Sammo’s darkest films, yet also one of the warmest, with plenty of room for silliness (the opening fight between rival unions) and superfluous action, including a showdown with Lau Kar-leung that is not only a great fight sequence, but is a deeply poignant tribute from one master to another (Sammo lets Lau win, of course).

Pedicab Driver exemplifies the most striking element in Sammo’s work (aside from the stunts, of course), and that is the bizarre, almost reckless mixing of tones and genres. Slapstick comedy rests uneasily alongside brutal violence, balletic grace and, occasionally, serious thought. Sammo’s cinema is populist, for all the good and bad that implies. It’s a cinema of and by the working class, the stunt crew, the men and women who’ve dedicated their life to performing impossible feats, one-upping each other in aggressively dangerous ways, all in the name of entertainment.

Occasionally he panders to the worst, most regressive elements of his society, as in the brutal final image of Encounters of the Spooky Kind, or in 1990’s Pantyhose Hero, which in its gay panic is hard to reconcile with the thoughtful examination of the intersection of poverty and patriarchy in Pedicab Driver. More usually though his films reflect the same generosity of spirit that led him to carve out spaces for friends and family in his industry.

In Winners and Sinners, Sammo is the constant butt of his friends’ jokes, he keeps his kung fu skills hidden from them, taking the abuse with patient good humor. When his love interest, Cherie Chung, asks him why he doesn’t stand up for himself, when he could easily beat them all up if he chose, he says that when he was a kid, he used to beat people up all the time, but he was alone. Now, even though they make fun of him, at least he has friends. It’s a sad story, but it might be Sammo at his most emotionally honest.

Pedicab Driver was Sammo Hung’s last great film as a director: in the 90s and beyond his best work would be as a choreographer (in Wong Kar-wai’s Ashes of Time, Donnie Yen’s Ip Man series, Stephen Fung’s Tai Chi 0 series) and supporting actor (Wilson Yip’s SPL: Sha Po Lang, Herman Yau’s The Legend is Born: Ip Man and Roy Chow’s Rise of the Legend). In 1997, he directed Jackie Chan in Mr. Nice Guy and stole Chan’s long-gestating idea for a kung fu Western to direct the sixth film in Tsui Hark’s Wong Fei-hung series, Once Upon a Time in China and America.

He didn’t direct another film for almost 20 years, until 2016’s quite lovely My Beloved Bodyguard, in which he plays a kindly, aged retired soldier attempting to protect his neighbor’s daughter from an endless gang of thugs. That same year he choreographed Benny Chan’s Call of Heroes, one of the finest old school ensemble kung fu films of recent years. In the works for the next year are the action direction of the third SPL film, to star Tony Jaa and Wu Jing (it opens in Hong Kong in just a few weeks), and a segment of Eight and a Half, the omnibus film project being coordinated by Milkyway Image, gathering together the greatest and most important directors of the last 40 years of Hong Kong cinema: Johnnie To, Tsui Hark, John Woo, Ann Hui, Ringo Lam, Patrick Tam, Yuen Woo-ping and Sammo Hung.