Chinese Cinema Today

A couple months ago I was asked to write this brief overview of the state of contemporary Chinese language cinema for the Estonian arts magazine Sirp. You can read this essay in Estonian on their website, and here, with their kind permission, is the original English language version.

Long one of the most vibrant and diverse film cultures in the world, the landscape of Chinese-language film has shifted dramatically over the last few years. Beginning with the handover of Hong Kong to Mainland China in 1997, the previously separate industries in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong have become increasingly enmeshed, and with the rapid expansion of theatrical exhibition on the Mainland and an economic boom that has opened up a massive potential audience, China is set to overtake the United States as the largest movie market in the world. Chinese companies have begun investing heavily in Hollywood productions, while American companies are seeking closer ties with their Chinese counterparts. A Chinese company (Wanda) now owns the largest chain of exhibitors in the US (AMC Theatres), as well as an American production company (in January of 2016 they purchased Legendary Entertainment, producers or co-producers of Jurassic World, Blackhat, Pacific Rim, and Christopher Nolan’s Batman films, among other blockbusters). Warner Brothers recently launched a new production house in cooperation with Chinese company CMC to remake Warners properties like Miss Congeniality, and release original films from veteran Hong Kong filmmakers Peter Chan and Stephen Fung along with Jackie Chan and Brett Ratner. CMC also has a joint venture with Dreamworks Animation, Oriental Dreamworks, which released Kung Fu Panda 3 this past January. Complicating this vast influx of cash into film production is China’s oft-arcane system of censorship and import quotas, which limit the kinds of films that can be shown in the nation’s theatres, as well as a tradition of gaming the system, if not outright corruption, in box office accounting. In the past few weeks, widespread fraud in the reporting of the grosses of Donnie Yen’s Ip Man 3 was discovered, leading to punitive action against the film’s local distributor and participating exhibitors.

With this dynamic and rapidly developing film culture, trying to predict what Chinese-language cinema is going to be like in five or ten years is a fool’s game. Instead, by taking a snapshot look at a few examples from the past year, we can get a sense of where the culture is at right now. From The Mermaid’s astounding box office success, to Go Away Mr. Tumor’s unique disregard for generic expectations; from Jia Zhangke’s idiosyncratic move toward the mainstream of the international art house with Mountains May Depart, to Bi Gan’s micro-budgeted, experimental and defiantly local debut Kaili Blues, Chinese cinema is one of the most financially lucrative and aesthetically innovative cinemas in the world.

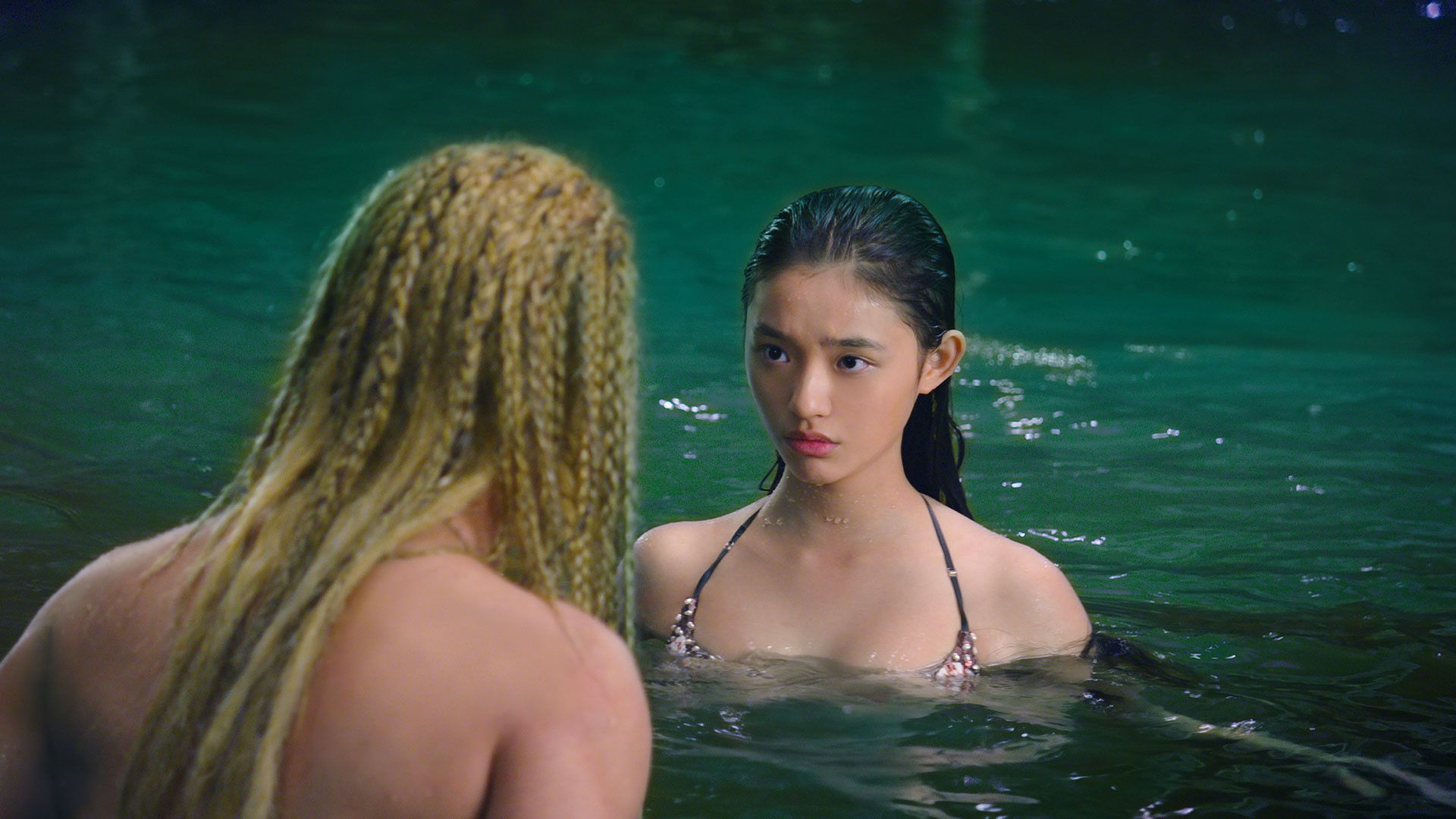

When Stephen Chow’s The Mermaid opened this past Lunar New Year (traditionally the busiest time for East Asian film-going) it was expected to compete with a pair of sequels with similarly strong Hong Kong pedigree, Wong Jing’s From Vegas to Macau III, starring Chow Yun-fat, and Soi Cheang’s Monkey King 2, starring Aaron Kwok and Gong Li. Those films racked up respectable returns, but The Mermaid simply blew them away with a phenomenal run that saw it become the highest grossing Chinese language film in history in less than two weeks, smashing the record set only last summer with Monster Hunt. A romantic comedy with a strong pro-environmental message, The Mermaid displays the slapstick genius that made Chow the dominant force in Hong Kong cinema in the 1990s, as well as a crossover hit in North America and beyond in the early 2000s with Shaolin Soccer and Kung Fu Hustle. Using modern digital effects to populate his film with half-human/half-fish creatures capable of ingenious acts of plastic hilarity (a mermaid assassin keeps getting stung with her own poisonous sea urchins, a half octopus man finds he must serve his own tentacles at a teppanyaki grill), Chow leavens his straightforward, almost trite message of ecological sanity with zany, often dark, humor and a compelling romance. Modern CGI has been a boon for Chow, the wild possibilities of computer effects allowing his most bizarre imaginings to take cinematic form. Freed from the tyranny of verisimilitude, his films have become more cartoonish in their physics, yet increasingly serious in message. His 2013 Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons, in addition to being a goofy tale of a monk fighting bizarre monsters, is also one of the more serious and thoughtful cinematic attempts to understand the ideals of Buddhism at a fundamental level, while The Mermaid is as outraged a lament for the effects rapid industrialization has had on the local environment that censorship will allow. Chow deftly navigates the potential political pitfalls by first making absurd the levels of ecological destruction wrought by his villains, but also by presenting both good and bad versions of the capitalist elites at fault for that destruction, a trick often used to deflect blame away from “the system” and towards a few bad eggs, giving the authorities a plausible deniability in the face of the film’s accusations. But still, it isn’t hard to imagine that the Beijing audiences that flocked to theatres to see the film recognize their poisoned and unbreathable air in the mermaids’ destroyed habitat.

Shortly after its Chinese release, The Mermaid opened in American theatres, under the auspices of Sony Pictures. However, despite Chow’s popularity in the States, the film was only released in a handful of theatres, with no promotion and no outreach to American critics (one critic talked to four different Sony representatives before he could find someone to confirm that the company was, in fact, releasing the film). Unlike American releases of European films, which play in art house theatres around the country, Asian films are increasingly released only in major urban multiplexes. These films are targeted exclusively to immigrant communities and are very rarely covered in the mainstream press. Over the past year, Chinese films by renowned filmmakers like Tsui Hark, Johnnie To, and Pang Ho-cheung have received these types of releases, playing on only a few dozen screens for a week or two. Frustrating as it is that so many films released this way fail to attract a wider following, as Kung Fu Hustle, Hero, and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon did in the early 2000s, this system is nonetheless a boon for fans of Asian cinema: those who know where to look can find a dazzling variety of films that would never make it onto the art house circuit. One such film was China’s official 2015 submission to the Academy Awards Foreign Language Film competition, Go Away, Mr. Tumor.

As the title implies, Go Away, Mr. Tumor is a goofy comedy about cancer. Mashing together the generic dynamics of the cute romantic comedy with the soul-searching seriousness of the medical melodrama, the film, directed by Han Yan and adapted from an autobiographical webcomic by Xiong Dun, is a fresh, energizing take on some of the hoariest of genre clichés. Bai Baihe stars as a young professional woman in Beijing who comes down with cancer and develops a crush on her doctor, played by Daniel Wu. The film follows all the familiar story beats: diagnosis, panic, treatment, acceptance, but mixes in the whimsicality of the romantic comedy, with Bai’s daffy dreamer trying various schemes to win the heart of the handsome and serious doctor. Throughout, Han makes extensive use of digital effects to literalize Bai’s fantasy world with magic realist moments of whimsy. Early in the film, Bai is dumped by her boyfriend and walks out into the cold Beijing streets, her sadness literally freezing everything, cars, buildings, people drinking coffee, that she walks past. The camera pulls back to a satellite view of the city, ice creaking across its grid of streets and lights, then it dissolves into a shot of Bai on a bench in front of a shopping mall, the lines and contours of the modern building matching perfectly the gridlines of the cityscape. It’s breathtaking and totally fake, as anti-realistic as any of Stephen Chow’s wildest images. This mixing of tones: the goofy and the sad, the seriousness of death and the silliness of a cartoon, is anathema to modern Hollywood, where screenplay manuals dictate consistency as a virtue and audiences can’t be expected to feel contradictory emotions. But it has a long tradition in Hong Kong (as it does in India, where the popular masala film throws every possible genre (action, comedy, romance, musical) into a single cinematic whirlwind). As Chinese cinema has opened up, many of Hong Kong’s generic tropes have migrated northward along with technicians and stars. The popular cinema that has emerged is not so much a break with that of Hong Kong, but a flashy updating of the old conventions and approaches. As recently as 2009’s Zhang Ziyi romantic comedy Sophie’s Revenge, a Chinese-Korean co-production, directed by Chinese-American Eva Jin, the Chinese film could be seen as a pale imitation of its Hong Kong cousins. It shares much of comic strip mentality and digital effects with Go Away Mr. Tumor, but with none of the sophistication or connection to real-life in Beijing: it simply isn’t as funny (or as sad, or as romantic) as the Hong Kong films of the same period. That’s no longer the case, as films like Go Away Mr. Tumor (along with action-comedies like Monster Hunt, Mojin: The Lost Legend and Tsui Hark’s The Taking of Tiger Mountain) have proven far more successful at melding Hong Kong style and approaches with the technological sophistication achievable with cash fronted by Mainland production companies.

At the same time, the independent Chinese cinema continues to thrive, despite obstacles put in place by the nation’s often frustrating censorship restrictions. Mainland Chinese film first gained international prominence in the late 1980s and 90s with a string of films by directors like Chen Kaige, Zhang Yimou and Tian Zhuangzhuang, the so-called Fifth Generation, directors who were the first to begin their careers after the end of the Cultural Revolution. They were followed, naturally, by a Sixth Generation in the 1990s and 2000s, directors who attempted to confront head-on the transition of post-Tiananmen China into a thriving capitalist economy. The most prominent of the Sixth Generation has been Jia Zhangke, whose films have played more frequently in the United States and Europe and at international film festivals than they have in his home country. For 20 years, with an austere, minimalist style crossing freely between fiction and non-fiction and occasionally shot through with striking moments of surreality, Jia has chronicled the nation’s development through the lens of his hometown of Fenyang, a medium-sized city in the northern Shanxi province. For most of his career, Jia’s films have gone undistributed in China, circulating only in bootlegged copies while government censors refused to approve his work. His 2013 film A Touch of Sin, a violent reimagining of several real-life tragedies that had recently taken place around the country, was apparently passed by the censors, but still went unreleased, lost in some kind or bureaucratic limbo. But in 2015, Jia’s Mountains May Depart was released on the Mainland, though with mixed returns. A three-part story following one love triangle over a period of 25 years, the film is an unabashed melodrama, and the first Jia film to be told with conventional close-ups, highlighting in particular the brilliant performance of lead actress Zhao Tao. The final third of the film baffled critics when the film premiered at Cannes. Set in Australia in 2025, it follows the teenaged son of two of the love triangle’s principals as he negotiates his alienation from his family and his homeland via an improbable love affair with his teacher, played by Taiwanese actress/director Sylvia Chang, the first proper movie star to feature prominently in a Jia film. This section of the film is performed primarily in English and its very deliberate strangeness is a profound departure for a filmmaker known for minimalist epics like Platform, Still Life, and The World. Yet Mountains May Depart is as much an engagement with the China of the present as those films were, and for all their moral and political seriousness, Jia’s films have always had a light touch, a love of pop music and a fascination with the weird in modern China (say the amusement park recreations of international landmarks in The World, or the inexplicable rocket ship in Still Life). Mountains May Depart’s two musical touchstones are “Go West” by the Pet Shop Boys and “Take Care” by Hong Kong star Sally Yeh, two cultures that crashed onto the mainland in the late 90s, driving China toward a baffling future.

As Jia and directors of his and prior generations cultivated international reputations on the festival and art house circuit, the newest generation has filled in the gap for independent Chinese cinema. After years of cancellations and interference from government administrators, the Beijing Independent Film Festival went international in 2015 with a slate of films touring cinemas in New York, Toronto, London, San Francisco, and Norway under the title Cinema on the Edge. Featuring movies like Luo Li’s Emperor Visits the Hell, Chai Chunya’s Four Ways to Die in My Hometown, and People’s Park and Yumen, two documentaries produced in collaboration with the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab, the program shows off the incredible diversity and innovation at work in independent Chinese cinema. Films like these, like those of filmmakers like Liu Jiayin (whose Oxhide films are some of the great undistributed works made anywhere in the world this century) or Xin Yukun’s Coffin in the Mountain, are shot cheaply and locally, with digital cameras, live sound and little to no special effects. Like Jia’s early work, they are particular to the specifics of a location, its culture and history. Four Ways to Die in My Hometown, for example, mixes centuries of folk tales and legends from its director’s remote Western province into one narrative world where the lines between past and present become blurred. Temporality breaks down as well in Bi Gan’s 2015 debut film Kaili Blues, which was just recently picked up for distribution by the adventurous new American company Grasshopper Films. What begins as a minimalist story about a small town doctor trying to keep his nephew from falling into a life of crime turns into something weird and magical during a trip to a nearby village. Central is a masterful 45 minute single take which transports the protagonist into an impossible village where the future and the past exist side by side, flattening a dense web of interconnected characters into a single cinematic space. It’s a daring and audacious debut, the kind of film that assures that though we can’t predict exactly where Chinese cinema is going, we can be sure it will be somewhere interesting.