Café Lumière (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 2003)

Café Lumière was supposed to be one part of an anthology made to honor the 100th anniversary of Yasujiro Ozu’s birth, but the other directors involved dropped out and so Hou Hsiao-hsien expanded his section into a feature. It’s set in Tokyo and tells the story of a young woman (Yôko) whose parents want her to get married, a common enough Ozu situation. The twist is that Yôko is pregnant and has absolutely no interest in marrying the father (“because he’s too close to his mother” she gives as a particularly biting explanation to her own mother). The film very obliquely follows this crisis, barely articulating the girl’s break from and then reconciliation with her parents. While Ozu’s films are full of people talking, often they end up saying more in the small spaces in-between their chatter. Hou builds his film around those empty spaces, cutting the dialogue down to the barest essentials of small talk (the father in Café Lumière barely says a word (if he even speaks at all) and the film’s plot, such as it is, is related in about three or four lines of dialogue) and leaves us instead with the distilled essence of Ozu, with everything he leaves unsaid. This approach is I think what J. Hoberman was getting at when he called it “an Ozu film in reverse — it’s mainly ambience ‘pillow shots,’ with bits of narrative serving as punctuation.”

Café Lumière also presented a stylistic challenge for Hou, in that he clearly wanted to pay homage to Ozu, but he also wanted to do more than simply copy another filmmaker’s style. There is no one in film history, at least not that I’ve encountered in mainstream narrative cinema, that has as idiosyncratic and identifiable style as Ozu, and as such, aping it would be pretty easy provided you’ve worked out all the rules (reading David Bordwell’s book should help). Instead of merely imitating, however, Hou melds some of the hallmarks of Ozu’s style with his own, far less rigid aesthetic. The result is neither an “Ozu” film nor a typical Hou film: it’s a Houzu film.

This melding can be seen right from the opening shot, which shows Yôko in her apartment:

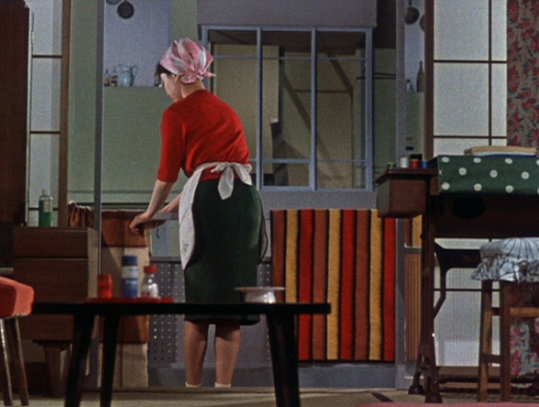

Compare this with a shot from the middle of Ozu’s final film, 1962’s An Autumn Afternoon, where we see the Chishu Ryu character’s daughter-in-law Akiko in her apartment:

The rectangular compositions are extremely similar. Both feature women looking out over balconies, backs to the camera with walls and windows delineating boxes and frames within the frame and with colorful bits of fabric breaking up the space. With Ozu, the colors are more vibrant, as is the music. Both are muted with Hou, befitting the quiet nature of the film in general (if I remember correctly, there’s no music in this scene, but the score in the rest of the film is a stark contrast to Ozu’s usual aimlessly jaunty melodies). This kind of composition is not unusual for Hou, such frontal squareness can be seen all the way back in The Boys from Fengkuei, his first “serious” film, but by the 2000s Hou had adopted a much more fluid and flowing style. The frames in Good Men, Good Women, Goodbye South, Goodbye, Flowers of Shanghai, and Millennium Mambo (the four films he made prior to Café Lumière) are much more cluttered and chaotic, a tangle of deep focus arcs and curves and lumps and shadows.

As the scene continues, Hou’s camera moves, a striking contrast to Ozu’s style, which, by the time of An Autumn Afternoon was almost completely immobile (a small amount of camera movement was a part of Ozu’s films consistently until his last five years or so, but the characterization of Ozu’s style as static lingers nonetheless, partially a by-product of his match cut-reliant editing style). It doesn’t move much, as I recall Yôko answers the phone and the camera wanders about more or less at random, maintaining the same middle distance from the action, but it’s enough to mark a break with the initial Ozuosity of the composition.

Probably the most explicitly Ozuvian shots in the film come a bit later, as Yôko returns to her parents’ house for a visit. We begin with a long immobile look through the house, and again the frame is divided by rectangles, this time not only by walls tunneling our sightline toward the in-deep-focus person in the distance, but also by open doors indicating that we are looking at three separate rooms, three planes of (potential) action: the kitchen in the far distance, the dining room in the middle, and a living room closest to us and the camera. Our eye is naturally drawn to the extreme distance where we see movement (the mom is cooking), so we barely register that there is another kind of door revealing a fourth space.

That is, until a car drives up (Yôko and her father have arrived), the movement again drawing our eye to the car’s reflection in the glass of the open front door. What once was three visual planes is now four. This kind of tiny arithmetical game is exactly the kind of trick Ozu, the most numerological of filmmakers, would have played. It also often provides the most whimsical element of a Hou film: the shocking reveal of detail that was there all along. Hou does this not only in compositions (my favorite is in Goodbye South, Goodbye, where what I assume is a pile of dirty clothes clumped on the floor turns out to be a sleeping Annie Shizuka Inoh) but also in the construction of his narratives (as in The Puppetmaster, where we see a long passage chronicling the romance between Li Tien-lu and a local prostitute, only to learn later that Li had had a wife and kids in another town the whole time).

Aside from the pleasurable, playful shock of recognition we get from seeing something that was already visible, the shot gives us a sense of the kind of 360 degree space that was an Ozu trademark and that Hou generally avoids: we are shown that not only is there depth into the screen before us, but also backwards, behind us. Later in the film, we get a reverse shot of the same setup, completing the three-dimensionality of the space, this time with each plane occupied by a different person or object (mother, father, cat, car). Reverse shots like this are an essential part of Ozu’s visual style but extremely uncommon in the Hou films of this period, in which the camera tends to drift laterally in relation to the action it is depicting, usually with pans and tilts but occasionally tracking into the on-screen space. Hou gives his space dimensionality through camera movement, whereas Ozu did it almost exclusively through framing and editing.